How to Break Your Bottlenecks with the TOC Five Focusing Steps

Why Every System Has a Bottleneck — and How to Break It

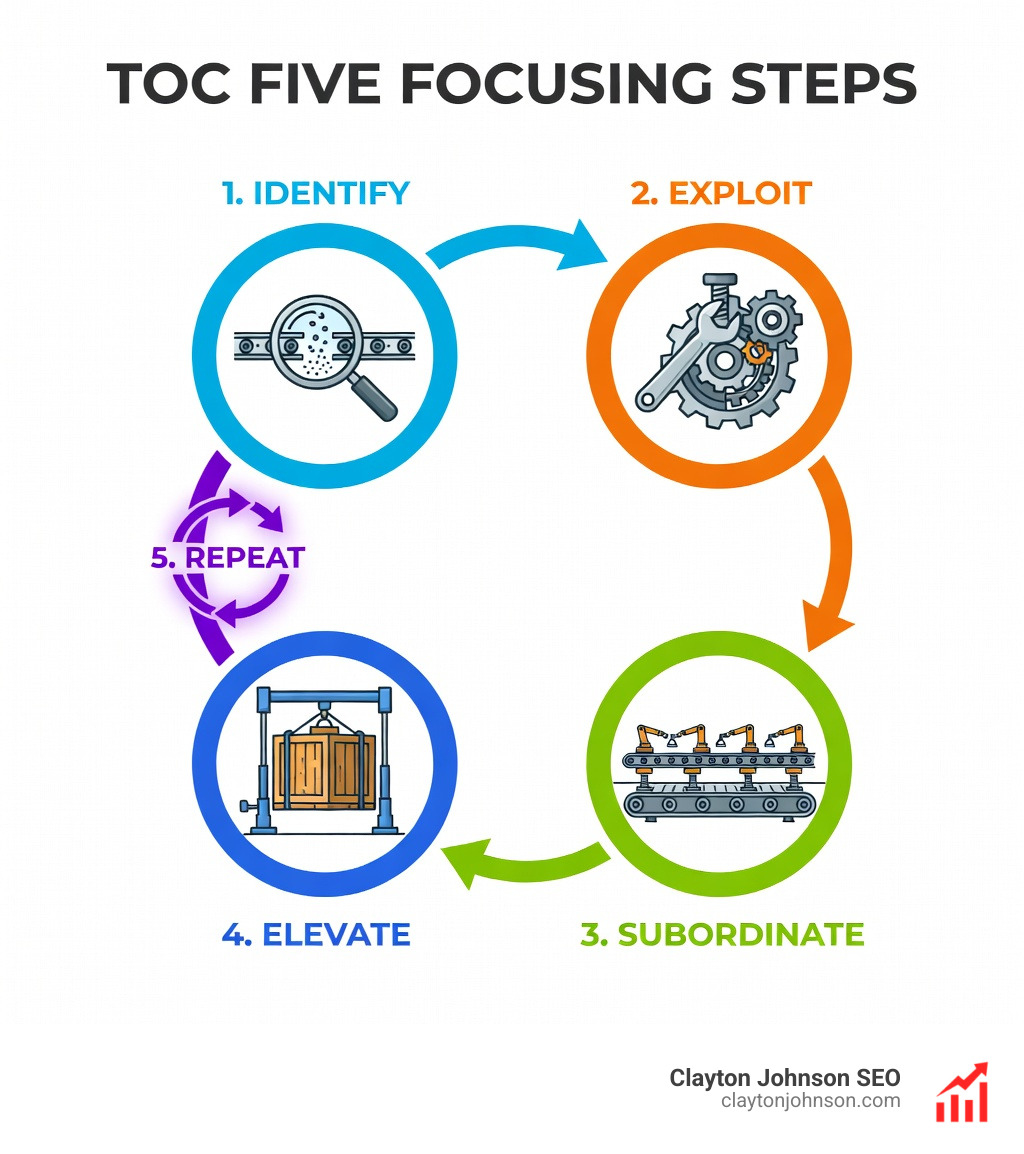

The TOC five focusing steps are a systematic methodology for identifying and eliminating the single constraint that limits your organization’s performance. Here’s the process:

- Identify the constraint — find the bottleneck limiting system throughput

- Exploit the constraint — maximize output from existing capacity

- Subordinate everything else — align non-constraints to support the bottleneck

- Elevate the constraint — invest to increase capacity only after exploitation

- Repeat — address the next constraint and prevent inertia

Most organizations fail to improve because they spread effort everywhere instead of focusing on the one thing holding them back. Dr. Eliyahu Goldratt introduced the Theory of Constraints (TOC) in his 1984 novel The Goal, showing that every process has a constraint—and fixing anything else is wasted effort.

The power of this approach is brutal clarity. Strengthening any link in a chain except the weakest is pointless. Yet most improvement programs ignore this principle, chasing local efficiencies that don’t move the system forward.

Implementing the first three steps properly exposes a minimum of 30% hidden capacity within the first few months—free, without investment. That’s not an optimization gain. That’s revealing capacity you already paid for but never used.

I’m Clayton Johnson, and I’ve applied the TOC five focusing steps to diagnose growth constraints in SEO systems, content workflows, and marketing operations—helping founder-operators focus effort where it actually compounds. The same principles that unlock manufacturing throughput unlock revenue engines.

Learn more about TOC five focusing steps:

- Change Management & Organizational Adaptability

- Kotter’s change management steps

What is the Theory of Constraints and the TOC Five Focusing Steps?

At its heart, the Theory of Constraints (TOC) is a management philosophy that views any manageable system as being limited in achieving more of its goals by a very small number of constraints. Think of your business as a chain; the TOC five focusing steps are the tools we use to find that one weak link and strengthen it.

The Core Concept: Focus Over Local Efficiency

In traditional management, we are taught to make every department “efficient.” We want the machines running 100% of the time and the employees busy every minute. TOC argues this is actually a recipe for disaster. If a non-bottleneck machine runs at 100% capacity while the bottleneck is slower, all you do is create a massive pile of unfinished work (WIP) that sits on the floor, eating your cash.

Instead, we use Throughput Accounting, which prioritizes three metrics:

- Throughput (T): The rate at which the system generates money through sales.

- Inventory (I): All the money that the system has invested in purchasing things which it intends to sell.

- Operating Expense (OE): All the money the system spends in order to turn inventory into throughput.

In this world, inventory is a liability, not an asset. To get real-time data on these metrics in a manufacturing environment, tools like Vorne XL help by providing automated, accurate data in less than eight hours. You can even follow Vorne on LinkedIn to see how real-time OEE data identifies these constraints.

The Four Types of Constraints

Not every bottleneck is a machine. We categorize constraints into four main buckets:

- Physical Constraints: Equipment capacity, lack of skilled people, or lack of raw materials.

- Policy Constraints: “The way we’ve always done it.” Rules, union contracts, or government regulations that inhibit flow.

- Paradigm Constraints: Deeply ingrained beliefs, like the idea that “we must keep everyone busy to be profitable.”

- Market Constraints: When your internal system works perfectly, but there aren’t enough customers buying the output.

The Five Steps of the TOC Process of Ongoing Improvement (POOGI)

The TOC five focusing steps aren’t a one-and-done project. They are part of a Process of Ongoing Improvement (POOGI). Before you start, however, you must ensure system stability. As W. Edwards Deming famously noted, you cannot improve an unstable system. You must first eliminate “special cause” variations—like erratic supplier deliveries or frequent machine breakdowns—before the true constraint reveals itself.

Once stable, the beauty of the TOC Flow is that it is self-correcting. If you misidentify the constraint, the system feedback will quickly show you that throughput hasn’t moved, allowing you to pivot.

The most staggering statistic in the research is this: properly implementing just the first three steps typically exposes a minimum of 30% hidden capacity within the first few months. This is “free” capacity—no new hires, no new machines, just better management of what you already have.

Step 1: Identify the TOC Five Focusing Steps Constraint

How do you find the “weakest link”? In a factory, it’s often easy: look for the pile of work. If there are 500 widgets sitting in front of Machine B and none in front of Machine C, Machine B is likely your constraint.

We recommend a “Gemba Walk”—literally walking the plant floor. Look for:

- Large piles of Work-in-Progress (WIP).

- Expeditors running around stressed.

- Long lead times for specific parts.

- Operators waiting for work (this indicates the constraint is upstream).

A Visual Factory setup, using Andon lights or digital displays, makes these bottlenecks visible to everyone instantly.

In knowledge work (like software development or SEO), constraints are invisible. You can’t see a pile of “unwritten code” on a desk. This is where Kanban boards and Value Stream Mapping become essential. You’re looking for the stage where tasks sit the longest.

Experienced managers often develop Fingerspitzengefühl—a German term for “finger-tips feeling.” It’s an intuitive sense of where the friction lies, developed by being at the center of the action rather than tucked away in an office.

Step 2 & 3: Exploit and Subordinate to the TOC Five Focusing Steps

Once you’ve found the constraint, Step 2 is to Exploit it. This means making sure the constraint is never idling. If a machine is the bottleneck, it shouldn’t stop for lunch breaks or shift changes. You ensure that only high-quality parts reach the constraint so it doesn’t waste time processing junk.

Step 3 is Subordinate. This is the hardest step for most managers. It means that every other part of the company must work at the pace of the constraint. If the bottleneck can only produce 10 units an hour, the upstream department should not produce 20 units an hour. If they do, they are just creating waste.

We use a method called Drum-Buffer-Rope (DBR):

- The Drum: The constraint. It sets the beat (pace) for the entire plant.

- The Buffer: A pile of work placed immediately in front of the constraint to ensure that if something goes wrong upstream, the “Drum” never stops.

- The Rope: A communication mechanism that releases work into the system only when the “Drum” processes something.

For those in the digital space, Agile consulting for constraints can help apply these DBR principles to manage uncertainty and protect your “sprint capacity” from being overwhelmed by non-essential tasks.

Step 4 & 5: Elevate and Repeat the TOC Five Focusing Steps

Only after you have squeezed every bit of capacity out of the constraint (Exploit) and aligned the rest of the system (Subordinate) should you move to Step 4: Elevate. This is where you spend money. You buy a second machine, hire a second specialist, or outsource the work.

Warning: Most people jump to Step 4 immediately. This is a mistake. It increases your investment risk and often just moves the bottleneck somewhere else without improving total throughput.

Finally, Step 5 is Repeat. Once you elevate a constraint, it will eventually stop being the bottleneck. The “weakest link” will move somewhere else—perhaps to the market (not enough orders) or to another machine. You must go back to Step 1 immediately.

The danger here is Inertia. Old rules that were created to manage the old constraint can become “Policy Constraints” for the new one. You have to be like a game of Whac-A-Mole; as soon as one constraint is broken, you move to the next. Sustaining success requires constant vigilance to ensure old habits don’t become the new bottleneck.

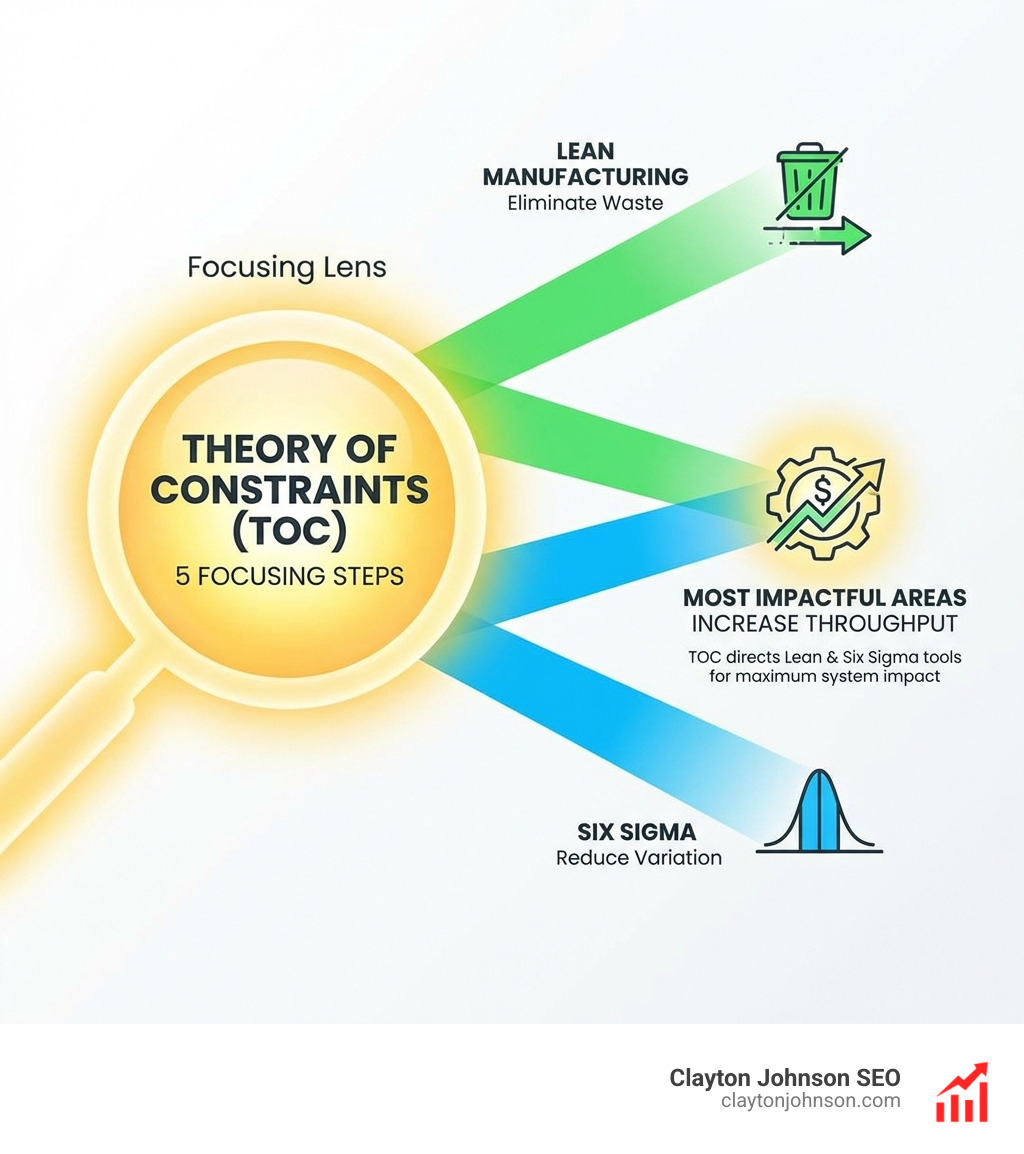

Integrating TOC with Lean Manufacturing and Six Sigma

A common question is: “Should I use TOC or Lean?” The answer is both.

We view the TOC five focusing steps as the “prioritization engine.” Lean and Six Sigma provide the “tools” to fix what TOC identifies.

| Feature | Theory of Constraints (TOC) | Lean Manufacturing | Six Sigma |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Increase Throughput | Eliminate Waste | Reduce Variation |

| Focus | The System Constraint | The Value Stream | Process Steps |

| Main Tool | Five Focusing Steps | 5S, Kanban, Kaizen | DMAIC, Statistical Tools |

| Perspective | Systems Thinking | Flow Thinking | Analytical Thinking |

How Lean Tools Support TOC

- 5S & Kaizen: Use these to Exploit the constraint by organizing the workspace so the operator never has to hunt for tools.

- SMED (Single-Minute Exchange of Die): Use this to Elevate the constraint by reducing setup times, allowing the bottleneck to spend more time “running” and less time “changing over.”

- TPM (Total Productive Maintenance): Essential for the constraint to ensure it never breaks down unexpectedly.

- Root Cause Analysis (5 Whys): Used when the “Buffer” is penetrated, helping you understand why work didn’t reach the constraint on time.

You can even find Lean Six Sigma templates to help document these improvements as you go.

Real-World Applications and Measurable Benefits

The TOC five focusing steps aren’t just for heavy industry. They work anywhere value is created.

The Laundromat Metaphor

Imagine a laundromat. You have 10 washers and 2 dryers. No matter how fast those washers are, you can only finish 2 loads of laundry at a time. The dryers are the constraint.

- Exploit: Make sure someone is there to flip the laundry the second the dryer stops. Don’t let a dryer sit empty.

- Subordinate: Stop starting new washes if the “dryer queue” is full. You’re just wasting floor space.

- Elevate: Buy a third dryer.

- Repeat: Now the washers might be the bottleneck.

Manufacturing Success

In a real-world contract electronics manufacturer, applying these steps to an ICT test cell (the constraint) led to a 28% increase in throughput and halved the lead time from 18 to 9 days—all while reducing WIP by 42%. This is why there are over 42,000 Vorne XL installations worldwide; people want to see these results in real-time.

Knowledge Work & Healthcare

In software development, the constraint might be “Senior Architect Review.” By subordinating (limiting the number of new features started), the team actually finishes more features because the Architect isn’t overwhelmed. In TOC in Healthcare, these steps are used to manage patient flow in ERs, identifying whether the constraint is bed availability, doctor triage, or lab results.

Frequently Asked Questions about TOC

What is the difference between a bottleneck and a constraint?

A bottleneck is a resource where the capacity is less than the demand placed upon it. A constraint is the primary bottleneck that limits the entire system from achieving its goal. Every constraint is a bottleneck, but not every bottleneck is a constraint (if it’s not the slowest part of the whole chain).

How do you identify a constraint in a service or digital environment?

Look for the “Wait-to-Start” time. In digital workflows, the constraint is usually where the backlog is the largest or where work sits in “Pending Review” for the longest time. Using a Kanban board with WIP limits will make this constraint “flash” almost immediately.

Why is subordinating non-constraints the hardest step to implement?

Because it’s counter-intuitive. It requires telling a productive employee to “stop working” or “slow down” because they are producing more than the bottleneck can handle. Most managers feel like they are losing money if people are idle, but in TOC, idle non-constraints are a sign of a well-balanced system.

Conclusion

At Demandflow, we believe that most companies don’t lack tactics—they lack structured growth architecture. The TOC five focusing steps provide exactly that: a blueprint for where to apply your energy for maximum leverage.

When you stop trying to “fix everything” and start focusing on the constraint, you move from chaotic activity to compounding growth. Whether you are optimizing a production line in Minneapolis or a digital marketing funnel, the “weakest link” principle remains undefeated.

If you’re ready to apply this level of structural clarity to your online presence, check out our SEO content marketing services. We don’t just write content; we build authority-building ecosystems designed to break through your market constraints.

Clarity leads to structure. Structure leads to leverage. And leverage leads to the kind of growth that feels like magic—but is actually just good physics.